In late August 1777, the American Army planned a raid on Staten Island. Intelligence available to the Americans suggested that the British forces there were primarily American Loyalist militia rather than British regular troops. Furthermore, the inexperienced Tories were stealing food and supplies from the local residents. A raid presented the opportunity to generate local goodwill as well as disrupt British raiding along the New Jersey coast.

About one thousand men partook in the raid on August 22, which began well. Surprised Loyalists fled the advancing Americans, who helped themselves to the arms and equipment left behind. The day was full of surprises as the Americans soon ran into a regiment of British Regulars, who quickly retreated to their fortifications. Thinking they had won the day, the American raiders turned to raiding, ceasing to be an effective fighting force. Meanwhile the British regulars had regrouped and went on the offensive, causing a general American rout.

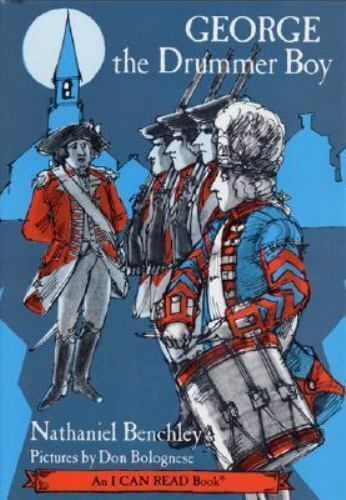

Plan of the redoubts at Richmond on Staten Island later in the war. Click image to view full size. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Major John Steward, a veteran of the Battle of Brooklyn led the rear guard, and rallied his men to buy time for the Americans to escape. A Marylander by the name of Captain William Wilmot described the scene in a letter:

thay came down on us with about 1000 of their herows, and attacked us with about 500 of their new troopes and hesions [Hessians] expecting I believe that thay should not receive one fire from us but to their grate surprise thay received many as we had to spair and had we had as many more thay should have been welcome to them, thay maid two or three attempts to rush on us, but we kept up such a blaze on them, that thay were repulsed every time, and not withstanding we was shure that we must very soon fall into their handes.

With the rear guard, numbering about 150 men, delaying the British, the bulk of the American force managed to escape. Wilmot continues:

When we see them running back from our fire there was such a houraw or hussaw from the one end of our little line to the other that thay could hear us quight across the river, but what grieved me after seeing that it was not the lot of many of us to fall and our ammunition being expended, that such brave men were obliged to surrender them selves Prisioners to a dasterley, new band of Murderrers, natives of the land [Loyalists], when our ammunition was all spent Major Sturd [Steward] took a whight hankerchief and stuck it on the point of his Sword, and then ordered the men to retreet whilste he went over to their [the British] ground, and surrendered, for he had never gave them an inch before he found that he had nothing left to keep them of[f] with.

Steward and the other captured Americans were put on the British prison barges and ships in New York Harbor. Such ships were notorious for their wretched conditions. An account from a Connecticut soldier turned prisoner Robert Shefield gives detail to the horror:

The heat was so intense that (the hot sun shining all day on deck) they were all naked, which also served the well to get rid of vermin, but the sick were eaten up alive. Their sickly countenances, and ghastly looks were truly horrible; some swearing and blaspheming; others crying, praying, and wringing their hands; and stalking about like ghosts; others delirious, raving and storming,—all panting for breath; some dead, and corrupting. The air was so foul that at times a lamp could not be kept burning, by reason of which the bodies were not missed until they had been dead ten days.

Steward would not endure the horror for long. Purportedly by bribing a British officer, the major managed to escape his prison ship, fled to New Jersey and was back with the Continental Army by the end of October.

Click here to read Steward’s full biography, and here for an incident involving Steward when he was a Lieutenant.

Nick Couto

Sources:

“General Sullivan’s Descent Upon The British On Staten Island—The Escape Of William Wilmot.” Maryland Historical Magazine, 6, no.2 (June 1911) p. 141-142; Some spelling modified for readability.

Patrick O’Donnell, Washington’s Immortals, The Untold Story of an Elite Regiment Who Changed the Course of the Revolution (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2016), 137-140;

Charles Royster, A Revolutionary People at War (Chapel Hill, N.C: University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 95.

Danske Dandridge, American Prisoners of the Revolution, ch.14 (1910) Project Gutenberg